Geography and History

REGISTRATION FORM

Overview | La Dolce Vita Itinerary | About Hotel Villa Beccaris

La Dolce Vita Pricing | Wines of the Piedmont Region | Geography & History of the Piedmont Region

Pre and Post Extensions | Travel Insurance | About Terroirs Travels

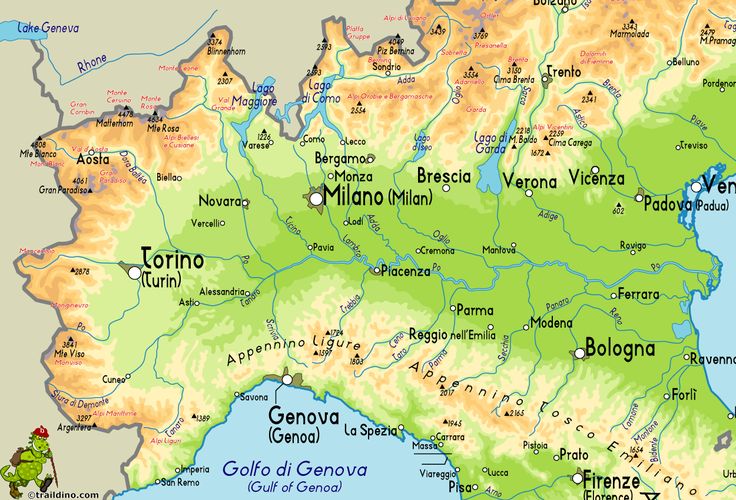

The Piedmont region is located in the foothills of the Alps forming a border with France and Switzerland. To the northwest is the Valle d’Aosta, to the east is the province of Lombardy with the Liguria region forming its southern border along the Apennines. In addition to the vast mountainous terrain, the Po Valley consumes a large area of available land-leaving only 30% of the region suitable for vineyard plantings. The valley and the mountains do contribute to the area’s noted fog cover which aides in the ripening of the Nebbiolo grape (which gets its name from the Piedmontese word nebbia meaning “fog”).

The Piedmont region is located in the foothills of the Alps forming a border with France and Switzerland. To the northwest is the Valle d’Aosta, to the east is the province of Lombardy with the Liguria region forming its southern border along the Apennines. In addition to the vast mountainous terrain, the Po Valley consumes a large area of available land-leaving only 30% of the region suitable for vineyard plantings. The valley and the mountains do contribute to the area’s noted fog cover which aides in the ripening of the Nebbiolo grape (which gets its name from the Piedmontese word nebbia meaning “fog”).

Although the winemaking regions of the Piedmont and Bordeaux are very close in latitude, only the summertime temperatures are similar: the Piedmont wine region has a colder, continental winter climate, and significantly lower rainfall due to the rain shadow effect of the Alps. Vineyards are typically planted on hillside altitudes between 490–1150 ft. The warmer south facing slopes are mainly used for Nebbiolo or Barbera while the cooler sites are planted with Dolcetto or Moscato.

The majority of the region’s winemaking (about 90%) takes place in the southern part of Piedmont around the towns of Alba (in Cuneo), Asti and Alessandria.

The majority of the region’s winemaking (about 90%) takes place in the southern part of Piedmont around the towns of Alba (in Cuneo), Asti and Alessandria.

The Piemonte wine region is divided into five broad zones:

Canavese – includes the areas around Turin such as Carema and Caluso

Colline Novaresi – in the province of Novara

Coste della Sesia – includes the area around Vercelli

Langhe – includes the hill country around the city of Alba and the Roero.

Monferrato – includes the areas around Asti and Alessandria

History

While Turin is the capital of the Piedmont, Alba and Asti are at the heart of the region’s wine industry. The wine making industry of the Piedmont played a significant role in the early stages of the Risorgimento with some of the era’s most prominent figures-like Camillo Benso, conte di Cavour and Giuseppe Garibaldi owning vineyards in Piedmont region and making significant contributions to the development of Piedmontese wines. The excessively high tariffs imposed by the Austrian Empire on the export of Piedmontese wines to Austrian controlled areas of northern Italy was one of the underlying sparks to the revolutions of 1848–1849.

While Turin is the capital of the Piedmont, Alba and Asti are at the heart of the region’s wine industry. The wine making industry of the Piedmont played a significant role in the early stages of the Risorgimento with some of the era’s most prominent figures-like Camillo Benso, conte di Cavour and Giuseppe Garibaldi owning vineyards in Piedmont region and making significant contributions to the development of Piedmontese wines. The excessively high tariffs imposed by the Austrian Empire on the export of Piedmontese wines to Austrian controlled areas of northern Italy was one of the underlying sparks to the revolutions of 1848–1849.

Camillo Benso was not only the first prime minister of the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia during the Risorgimento but he was also a prominent vineyard owner who introduced many French viticultural techniques to the region.

As in most of Italy, native vines are abundant in the land that the Ancient Greeks called Oenotrua (meaning “land of vines”) and was subsequently cultivated by the Romans. With its close proximity, France has been a significant viticultural influence on the region, particularly Burgundy, which is evident today in the varietal styles of most Piedmontese wines with very little blending.

One of the earliest mention of Piedmontese wines occurred in the 14th century when the Italian  agricultural writer Pietro de Crescentius wrote his Liber Ruralium Commodorum. He noted the efforts of the Piedmontese to make “Greek style” sweet wines by twisting the stems of the grapes clusters and letting them hang longer on the vine to dry out. He also noted the changes with trellising in the region with more vines being staked close to the grounds rather than cultivated high among trees in the manner more common to Italian viticulture at the time. In the 17th century, the court jeweller of Charles Emmanuel I, Duke of Savoy earned broad renown for his pale red Chiaretto made entirely from the Nebbiolo grape.

agricultural writer Pietro de Crescentius wrote his Liber Ruralium Commodorum. He noted the efforts of the Piedmontese to make “Greek style” sweet wines by twisting the stems of the grapes clusters and letting them hang longer on the vine to dry out. He also noted the changes with trellising in the region with more vines being staked close to the grounds rather than cultivated high among trees in the manner more common to Italian viticulture at the time. In the 17th century, the court jeweller of Charles Emmanuel I, Duke of Savoy earned broad renown for his pale red Chiaretto made entirely from the Nebbiolo grape.

During the Risorgimento (Italian unification) of the 19th century, many Piemontese winemakers and land owners played a pivotal role. The famous Italian patriot Giuseppe Garibaldi was a winemaker who in the 1850s introduced the use of the Bordeaux mixture to control the spread of oidium that was starting to ravage the area’s vineyards.